The Medical Careers expo at The Canberra hospital last week was a opportunity to showcase the range of career opportunities that an anaesthesia Fellowship offers – slideshow below…

https://vimeo.com/218244883

The Medical Careers expo at The Canberra hospital last week was a opportunity to showcase the range of career opportunities that an anaesthesia Fellowship offers – slideshow below…

https://vimeo.com/218244883

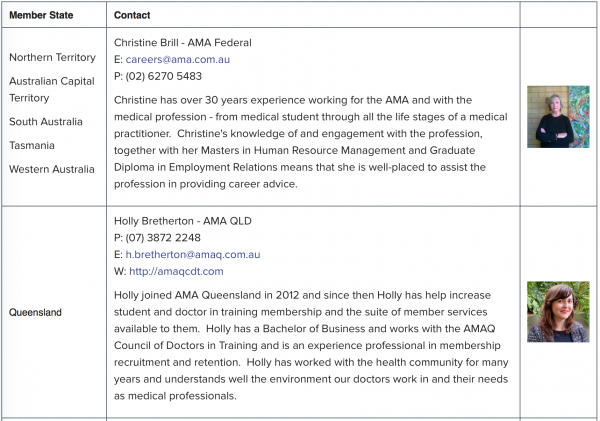

Christine Brill is the AMA’s Federal Career adviser for the AMA Career Advice Hub.

Christine Brill is the AMA’s Federal Career adviser for the AMA Career Advice Hub.

The AMA Career Advice Hub has been developed to provide advice, support and guidance for those planning medical careers.

The Career Advice Hub is for high school and college students, medical students, new medical graduates, pre-vocational and vocational trainees, qualified practitioners and international medical students and graduates.

There are handy sections for CV presentation and polishing and tips on job interview technique, self-care and financial advice – just what anaesthetic registrars will be needing after their exams….

Have a closer look at https://ama.com.au/careers!

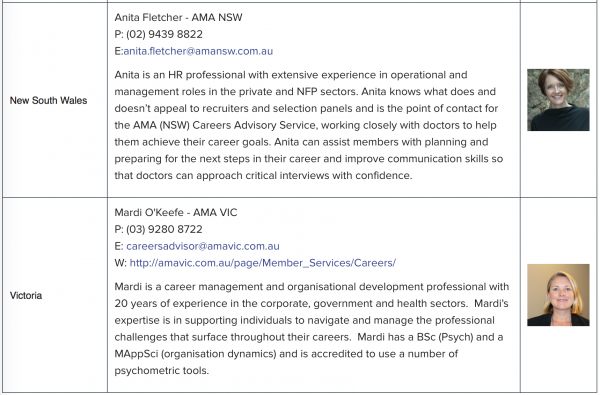

The AMA’s Career Advice service and Resource Hub are there to assist! Contact the AMA Career Adviser (Christine) on careers@ama.com.au or contact the State or Territory AMA advisers listed below for details on their one-to-one career advisory services. (The links below are not active).

A recent article in the Health and Medicine section of The Conversation website:

https://theconversation.com/a-short-history-of-anaesthesia-from-unspeakable-agony-to-unlocking-consciousness-74748?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Latest from The Conversation for May 2 2017 - 72895553&utm_content=Latest from The Conversation for May 2 2017 - 72895553+CID_67e04e15f258af049914043ee1254fff&utm_source=campaign_monitor&utm_term=A short history of anaesthesia from unspeakable agony to unlocking consciousness

Author David Liley Professor, Centre for Human Psychopharmacology, Swinburne University of Technology

We expect to feel no pain during surgery or at least to have no memory of the procedure. But it wasn’t always so.

Until the discovery of general anaesthesia in the middle of the 19th century, surgery was performed only as a last and desperate resort. Conscious and without pain relief, it was beset with unimaginable terror, unspeakable agony and considerable risk.

Not surprisingly, few chose to write about their experience in case it reawakened suppressed memories of a necessary torture.

was by Fanny Burney, a popular English novelist, who on the morning of September 30, 1811 eventually submitted to having a mastectomy:

When the dreadful steel was plunged into the breast … I needed no injunctions not to restrain my cries. I began a scream that lasted unintermittently during the whole time of the incision … so excruciating was the agony … I then felt the Knife [rack]ling against the breast bone – scraping it.

But it wasn’t only the patient who suffered. Surgeons too had to endure considerable anxiety and distress.

John Abernethy, a surgeon at London’s St Bartholomew’s Hospital at the turn of the 19th century, described walking to the operating room as like “going to a hanging” and was sometimes known to shed tears and vomit after a particularly gruesome operation.

Discovery of anaesthesia

It was against this background that general anaesthesia was discovered.

A young US dentist named William Morton, spurred on by the business opportunities afforded by technical advances in artificial teeth, doggedly searched for a surefire way to relieve pain and boost dental profits.

His efforts were soon rewarded. He discovered when he or small animals inhaled sulfuric ether (now known as ethyl ether or simply ether) they passed out and became unresponsive.

A few months after this discovery, on October 16, 1846 and with much showmanship, Morton anaesthetised a young male patient in a public demonstration at Massachusetts General Hospital.

The hospital’s chief surgeon then removed a tumour on the left side of the jaw. This occurred without the patient apparently moving or complaining, much to the surgeon’s and audience’s great surprise.

So began the story of general anaesthesia, which for good reason is now widely regarded as one of the greatest discoveries of all time.

Anaesthesia used routinely

News of ether’s remarkable properties spread rapidly across the Atlantic to Britain, ultimately stimu- lating the discovery of chloroform, a volatile general anaesthetic.

According to its discoverer, James Simpson, it had none of ether’s “inconveniences and objections” – a pungent odour, irritation of throat and nasal passages and a perplexing initial phase of physical agitation instead of the more desirable suppression of all behaviour.

Chloroform subsequently became the most commonly used general anaesthetic in British surgical and dental anaesthetic practice, mainly due to the founding father of scientific anaesthesia John Snow, but remained non-essential to the practice of most doctors.

This changed after Snow gave Queen Victoria chloroform during the birth of her eighth child, Prince Leopold. The publicity that followed made anaesthesia more acceptable and demand increased, whether during childbirth or for other reasons.

By the end of the 19th century, anaesthesia was commonplace, arguably becoming the first example in which medical practice was backed by emerging scientific developments.

Anaesthesia is safe

Today, sulfuric ether and chloroform have been replaced by much safer and more effective agents such as sevoflurane and isoflurane.

Ether was highly flammable so could not be used with electrocautery (which involves an electrical current being passed through a probe to stem blood flow or cut tissue) or when monitoring patients electronically. And chloroform was associated with an unacceptably high rate of deaths, mainly due to cardiac arrest (when the heart stops beating).

The practice of general anaesthesia has now evolved to the point that it is among the safest of all major routine medical procedures. For around 300,000 fit and healthy people having elective medical procedures, one person dies due to anaesthesia.

Despite the increasing clinical effectiveness with which anaesthesia has been administered for over the past 170 years, and its scientific and technical foundations, we still have only the vaguest idea about how anaesthetics produce a state of unconsciousness.

Anaesthesia remains a mystery

General anaesthesia needs patients to be immobile, pain free and unconscious. Of these, unconsciousness is the most difficult to define and measure.

For example, not responding to, or then not remembering, some event (such as the voice of the anaesthetist or the moment of surgical incision), while clinically useful, is not enough to decisively determine whether someone is or was unconscious.

This chloroform inhaler was the type John Snow used on Queen Victoria to ease the pain of childbirth. Chloroform vapours were delivered down a tube via the brass and velvet face mask. Science Museum, London/Wellcome Images/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

We need some other way to define consciousness and to understand its disruption by the biological actions of general anaesthetics.

Early in the 20th century, we thought anaesthetics worked by dissolving into the fatty parts of the outside of brain cells (the cell membrane) and interfering with the way they worked.

But we now know anaesthetics directly affect the behaviour of a wide variety of proteins necessary to support the activity of neurones (nerve cells) and their coordinated behaviour.

For this reason the only way to develop an integrated understanding of the effects of these multiple, and individually insufficient, neuronal protein targets is by developing testable, mathematically formulated theories.

These theories need to not only describe how consciousness emerges from brain activity but to also explain how this brain activity is affected by the multiple targets of anaesthetic action.

Despite the tremendous advances in the science of anaesthesia, after almost 200 years we are still waiting for such a theory.

Until then we are still looking for the missing link between the physical substance of our brain and the subjective content of our minds.

The AIDS Garden of Reflection was one of four connected gardens opened over the weekend in the Gallery of Gardens at the Canberra Arboretum. It was generously supported by local Canberra charitable foundation the John James Foundation.

The Garden is a living tribute to those lost to AIDS and in support of those living to HIV. The structure has been planted with wisteria – designed to create a calm and comforting environment.

An excellent timeline of the history of anaesthesia can be found at

http://www.asa.org.au/UploadedDocuments/HALMA/Anaesthesia%20History%20Timeline%202017%20Jan%202.pdf

The ASA’s Harry Daly museum even takes time to commemorate Valentine’s Day (from an ASA twitter post by Rebecca Anne Lush)

The Final Examination preparation Boot Camp was reprised in Canberra during February after its successful debut in 2016.

This is one of the range of events the ASA supports which are aimed at meeting the needs of trainees. The weekend was again open to all exam candidates.

Current Final Examiners prepared presentations and participated in panel discussions. They were available throughout the weekend to answer questions to the group and to address individual concerns.

Vivas, videos, investigations, performance tips and statistics were covered over the weekend…Support from the ASA Membership Events Coordinator Jennifer Ellis and the John James Foundation particularly contributed to the smooth-running of the weekend.

Feedback from delegates and faculty was overwhelmingly positive. Suggestions for improvement make it look like we’re going to have to do it again in 2018 …3+4 Feb!

Thank you to all participants and best wishes to candidates for their exams.

Vida Viliunas – Convenor

Final exam candidates are preparing for their exams next week in Sydney. Anaesthetic registrars all over Australia and the region have been studying and rehearsing their techniques for their viva examinations.

Our study group in the ACT has been concentrating on themes that help anaesthetists in training for exams and will serve them for their careers as doctors.

We have been concentrating on sensible and practical approaches aimed at reassuring both patients and examiners! The responses reflect safe, sensible, evidence based practice – that is what we do in our clinical work.

We made a video illustrating some final exam tips : see also the trainee section.

https://vimeo.com/187271146

A recent article in The Guardian highlights the anonymous nature of the work of anaesthetists: “…if the surgeons are the blood, we are the brains…”.

The piece – appropriately by ‘Anonymous’ – starts with the sentence: “You have to get used to being invisible as an anaesthetist”…and highlights the common facts that “patients always remember the name of their surgeon, never that of their anaesthetist…but also what we do:

“We assess people’s fitness for surgery, how likely they are to suffer complications, and support them through the operation itself and into the postoperative period.”

The full article can be found here:

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/sep/12/secret-life-anaesthetist-surgery-doctor

You have to get used to being invisible as an anaesthetist. A large percentage of the public has no idea that we’re medically qualified. I’ve been asked how many GCSEs you need to be an anaesthetist. In fact our training is as long as that of a surgeon. It takes seven years of specialist studies after you’ve already completed two years of basic general training; and that’s after five or six years at medical school.

Patients always remember the name of their surgeon, never that of their anaesthetist. But it’s still a hugely rewarding job. We’re everywhere in the hospital. In theatre obviously, but also in intensive care, on the wards, in the emergency department, and in the pain clinic, with those who are really suffering. We assess people’s fitness for surgery, how likely they are to suffer complications, and support them through the operation itself and into the postoperative period.

If there’s an emergency during an operation the team looks to the anaesthetist for leadership. If you panic, it spreads

When you first start anaesthetising patients early on in your career it’s terrifying. You know that if you get it wrong you might kill someone. Our drugs stop people breathing and it’s our job to take over that function. Even after nine years I still get a frisson of nerves in some situations. I hide it though; it’s an important part of the job to stay calm at all times. If there’s an emergency during an operation the team looks to the anaesthetist for leadership, as the surgeon is often too focused on fixing the immediate problem. If you panic, it spreads and the team loses the ability to function efficiently.

Anaesthesia is a very safety-oriented speciality; we’ve led the way in reducing patient harm by looking at human factors, using simulation training and reporting “near misses”. By sharing episodes where a patient has nearly come to harm, we hope to address the causes and prevent actual harm from occurring in the future. We’ve embraced ideas from aviation and other high-reliability industries about how a team functions effectively. We try to flatten the hierarchy in theatre so that the least qualified individual can raise concerns without feeling intimidated. This makes it especially frustrating when patients come to harm after they leave your care because the rest of the system is struggling to cope.

There are so many gaps in rotas of doctors, nurses and the wider healthcare team, and the proposed junior doctor contract changes will only make this worse. The outlook for patients who suffer complications after surgery is determined not by the presence of the complication, but by how quickly it is picked up and dealt with. This simply can’t happen when workloads are too high.

I look after one patient at a time. This ability to offer a premium level of care is one of the reasons I became an anaesthetist in the first place. On the wards each doctor will be responsible for up to 30 people a day, and even more at night. I can see with each heartbeat what the patient’s blood pressure is in the operating theatre; on the wards, it might only be checked once every four hours.

The speciality is a broad church, so there is room for all personality types. But given the precision involved there is perhaps a tendency to obsessive traits. I’ve worked with colleagues who have a 10-minute ritual for putting in an intravenous cannula that had to be completed in the correct sequence. Our postgraduate exams are renowned for being tricky but they are really a test of commitment. We’re experts in physiology, pharmacology, and physics; we have to know about everything from cellular respiration to how our drugs work, to the internal workings of a defibrillator.

Patients are usually nervous when they arrive in my anaesthetic room. It’s an exercise in trust to place your whole life in the hands of others. Every anaesthetist will have their spiel, some small talk to distract the patient from their imminent surgery. I ask them about family, talk about their favourite place to visit, what they do for a living. I modify my “going to sleep” talk depending on the small talk that’s gone before. If they love travelling, I’ll talk about a white sandy beach, with crystal clear waters, a gentle breeze. The more nervous they are, the longer they take to go to sleep. Many young, usually male, patients have commented as the drugs take effect that it feels just like a Saturday night. I’ve also been asked if I liked to have sex in a vest – I decided not to pursue what he meant by that when he woke up.

Every anaesthetist has a secret weapon when working in the operating theatre. We always work with an assistant, who might be a nurse or an operating department practitioner (ODP). The very best of them could do my job without thinking twice, but they choose even greater anonymity than the anaesthetist enjoys. Many a time I’ve had my bacon saved by an astute ODP. Some appear to have powers of extrasensory perception; I turn to ask for something and there it is in my hand.

I’ve also worked with many theatre colleagues with a wicked sense of humour. Before my first unsupervised operating shift, I confessed to the ODP that I’d never worked alone before. He paused and stuttered that neither had he, it was his first day at work, being newly qualified. I spent the entire day terrified that some disaster would befall us, and we wouldn’t be up to the challenge. At the end of the day he came clean – he’d been doing the job for 20 years.

Frustrations creep in to the job when the system fails. I often arrive at 7.30am (30 minutes before my shift begins), so I can find space on the pre-op ward to see my patients in private, find out their history and take the time to address any concerns. It’s then immensely distressing when operations are cancelled due to lack of beds, or lack of notes, or the surgeon’s been double booked, or you are moved to another job at short notice. Anaesthesia can also become routine; it’s a far cry from the early days of the speciality when unpredictable drugs were used without monitoring. If the patient is fit, it’s rare for them to come to harm from a general anaesthetic.

Anonymous

It is important to have other interests to distract from the stresses, strains and occasional boredom of the job. In my spare time I’m a volunteer doctor for the ambulance service. Being under a car in a ditch in the rain at 2am is very different from the bright lights of the operating theatre. Some of my colleagues are real polymaths. There are painters, musicians, novelists, as well as some quite serious sports people. The coffee room in the morning is the preserve of the middle-aged man in lycra. We see every day the damaging effects of too little aerobic fitness, so we’re staving off our own mortality.

The best bits? Reassuring nervous patients, rendering labouring women pain-free with the magic of epidural analgesia and, of course, merciless surgeon baiting. I’ll ask if they need me to Google instructions for the operation, or if they’ll be finished before new year. We say there’s a blood-brain barrier between the surgeon and the anaesthetist: they’re the blood, and we’re the brains.

Stephen Zheng has prepared an informative TEDed video on the subject – one of the best that I have seen!

http://ed.ted.com/lessons/how-does-anesthesia-work-steven-zheng#review